Aaron and the Golden Calf: Saint, or Sinner?

**This D'var Torah was written for Rabbis for Human Rights…Rav Barry

How could the high priest Aaron collude with the Jewish people in making a Golden Calf? It’s hard to believe, especially right after the people had witnessed miracles from God, like the plagues in Egypt and the parting of the Red Sea. Yet that is exactly what we read in this week’s Torah reading, Ki Tisa, from the book of Shmot (Exodus). Idol worship, led by none other than the Cohen Gadol, the high priest, himself!

Here’s how the story goes. The time: shortly after leaving Egypt. Moses goes up on Mount Sinai to receive the 10 Commandments from God, and when Moses is delayed coming down from the mountain the people tell Aaron, “…Make us gods, which shall go before us; we have no idea what happened to this Moses guy who brought out us out of Egypt.”

Aaron’s reply is “take the golden earrings from your wives, your sons, your daughters, and bring them to me.” So the people bring their gold to Aaron and he takes it, and the Torah tells us that he fashioned a molten calf. The people say “These are your gods, O Israel, which brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” And when Aaron sees it, he builds an altar before it; and Aaron proclaims “Tomorrow is a feast to the Lord.” And the people get up early on the next day, and offer burnt offerings, and peace offerings; and then the people sit down to eat and to drink, and rise up to play.

Meanwhile, up on the mountain, God saw what was going on, and angrily told Moses “Go down; for your people, whom you brought out of the land of Egypt, have corrupted themselves; They have turned aside quickly from the way which I commanded them; they have made them a molten calf, and have worshipped it, and have sacrificed to it, and said, ‘These are your gods, O Israel, which have brought you out of the land of Egypt’…”

We read this story, and the people of Israel seem impatient, unfaithful, and in a hurry to turn astray. Aaron, the high priest, seems just as ready to act the role of high priest to a golden calf as he is to serve as high priest to the Lord our God.

But there is another way to tell the story. Drawing on sources in the Talmud and Midrash, the story comes out very differently:

The people saw that Moses was late coming down from the mountain. Moses said he would be gone 40 days, and people were sure that the 40 days were up. They were confused because Satan had come and confused them, displaying an image of darkness and gloom. The people saw this as meaning that Moses must have died up on the mountain, and they were afraid. The people felt that only a god could lead them as well as Moses had led them, and they needed a physical representation of that god, just as Moses had been present physically.

The people told Aaron “…Make us gods, which shall go before us; we have no idea what happened to this Moses guy who brought out us out of Egypt.” Aaron was desperate to try and delay them, so he told them, “take the golden earrings from your wives, your sons, your daughters, and bring them to me.” Aaron figured that women and children would be reluctant to part with their gold, and in the meanwhile maybe Moses would come down from the mountain. But the people did not delay, they rapidly gave Aaron their gold. So Aaron took the gold and threw it into the fire.

Now when the people of Israel left Egypt they were accompanied by an “erev rav,” by a large mixed multitude of other people who were eager to leave Egypt. Amongst this mixed multitude were skilled sorcerers, and when Aaron threw the gold into the fire they used witchcraft to create the Golden Calf. Aaron was startled when the Golden Calf came out of the fire and these foreigners said “These are your gods, O Israel, which brought you up out of the land of Egypt.”

When Aaron saw the people were eager to worship the Golden Calf he took it on himself to build an altar, figuring he could do it slowly, and perhaps Moses would finally get down from the mountain before the people could actually worship it. He also figured it’s better that he should build the altar and take the blame for it then for all of Israel to take the rap. He then told the people, “tomorrow is a feast to the Lord,” hoping Moses would return, and the people would forget all about the Golden Calf and would return to the Lord.

God saw what was going on, and angrily told Moses “Go down; for your people, whom you brought out of the land of Egypt, have corrupted themselves.” By this God meant “Your people, that mixed multitude you decided to bring out of Egypt, not My people,” i.e., the Israelites.

Same story – but a very different conclusion. In the first version the people of Israel are a bunch of sinners, and Aaron is their ringleader. In the second version, the people of Israel are innocent bystanders and Aaron is a hero trying to prevent the people from falling into idol worship. The Midrash even blames God for letting the people collect so much gold from the Egyptians – God should have known the people would be tempted to sin with so much gold!

Why did the later rabbis put such a “gloss,” do such a job of “spinning” the tale told in the Bible? It’s probably at least in part because of a natural desire to see one’s ancestors as honorable, and a tendency we all have toward scape-goating, to blame others for our own faults.

It’s bad enough when that kind of re-telling of a story happens within a context of talking to yourself – and that’s what the Midrash is – the Jewish people telling stories to themselves to try to make sense of their history and traditions. But when you have two different peoples telling competing stories of the same events, two peoples who are thrown together in a contentious relationship, the power of the different stories is a real barrier to mutual understanding and peace. And nowhere is this problem more pronounced than in the different versions of the story of the founding of the State of Israel that are told by Israelis and Palestinians.

How do you make peace with someone whose entire view of recent history is COMPLETELY different than yours?

For Jews, 1948 stands out as one of our finest hours – tiny, beleaguered Israel heroically stood up to vastly superior Arab forces in the War of Independence which gave birth to our dream of 2000 years, an independent Jewish state in Palestine.

For Palestinians the war of 1948 is called “Al-Nakba,” “The Catastrophe,” a time when the colonizing Zionists, with international support, expelled hundreds of thousands of Arabs from their homes and turned them into refugees.

The versions of the period leading up to 1948 are equally out of synch:

The Jewish version: There has been a continuous Jewish presence in Israel going back to the days of Joshua. At times our presence was small in number and we were persec

uted, but we’ve always been there. In the 1800s, wealthy Jews from the West, like the Rothschilds and Montefiore, began to buy up land in Israel, much of which had been vacant, or swamps, with the goal of bringing Jews to settle and build the land. The idea was to bring “a people without a land to a land without a people.” Jews living miserable lives in places like Ukraine, Russia, and Poland, were encouraged to move to Israel “livnot u'l'hibanot” to build and be built: to build a country, and at the same time to build themselves into a new kind of Jew— not a yeshiva bucher or a pale-faced ghetto dweller,, but a farmer and builder, working the land, with a plow in one hand and a gun in the other.

The Palestinian version: in the late 19th century they were peacefully minding their own business, living in a country where they had lived for centuries if not millennia, when imperial colonizers started buying up land from absentee landlords, driving the local inhabitants off of land they had worked for generations. Zionists, people who came from Europe and knew little about Palestine or its people, came to take the land away from its rightful inhabitants. Zionist literature openly describes plans to expel the Arabs and Judaize the country. The Zionists never intended to share the land with its people – the Palestinians.

How can people with such completely different views of history reconcile their views sufficiently to make peace with each other?

I would suggest that It’s okay for different people to see the same facts in a different light. The Torah tells us shivim panim latorah, there are 70 faces to the Torah. We can agree on the facts – in the late 1800s Jews bought land from absentee Turkish landlords, and Jews from Eastern Europe came and settled on that land. Palestinians will have a hard time ever seeing that as anything other than a colonialist imposition; Jews will have a hard time ever seeing that same fact as anything other than the fulfillment of our ancestors’ dreams of nearly two thousand years, our return to our homeland.

One of the things I appreciate about my work with Rabbis for Human Rights is that it affords me the opportunity to meet with Palestinians from the West Bank and to hear their story. It’s one thing to read about the problems facing farmers in the West Bank in the newspaper; it’s another thing completely to hear it first hand, or even more powerfully, to experience the problems in real time.

But hearing their story doesn’t necessarily invalidate my story. Or vice verse; a few weeks ago Palestinians in Ni’lin, a West Bank village that has been the site of many confrontations, put together an exhibition commemorating the Holocaust on International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Understanding our story does not cause them to give up on theirs. As described in an article on “Middle East Online” Hassan Moussa, the organizer of the exhibition, says the people of Ni'lin have opted to complement their demonstrations with something "to show the Israelis that we feel sorry for them." As a Palestinian activist, Moussa says he also wants to convey his suffering: "My suffering will not lead to peace. When I lose my land, it's like losing your heart from your body." When we hear the other side’s story, and truly understand it, we are likelier to feel sympathy and a greater desire to make peace.

I don’t believe we need to try and push the two stories together into one story we agree on. People have different perspectives, and that’s OK. But what should happen is our narratives should inform each other.

For peace to come the Jews need to understand that Palestine was not “a land without a people.” That attitude for too long let Israel ignore the substantial Arab population that was on the land before the Zionists arrived. And the Palestinians have to understand that Zionism is not colonialism. Many Palestinians think of the arrival of Jews in Israel as a colonial phenomenon, like the Belgians going into the Belgian Congo. Some think that just as other countries have managed to throw out foreign colonizers, they too can get rid of the Jewish colonizers. But unlike the Belgians who left the Belgian Congo, there is no other place for the Jews to go. Israel IS our home. The national language we speak in Israel is not some European import: Hebrew is a native cousin of Arabic. Our ancestors, as well as theirs, built the houses and the fortresses and the places of worship, our forefathers, as well as theirs, are buried in the tombs. For we and the Palestinians are part of one big dysfunctional family that goes back to Isaac and Ishmael who struggled over the affection of their father Abraham; in the next generation, Jacob and Esau, the struggle began even in the womb!

There’s no point in talking about who was here first: we both were, for we’re both part of the same family tree. The Jews aren’t going “back to” Europe and the Arabs aren’t going to move to Jordan. The Arabs ARE home — and so are we. Now we need to figure out how to share our common abode.

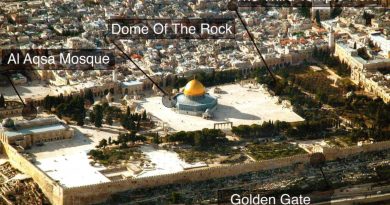

It is perhaps especially fitting that Herod the Great – the greatest builder in the history of Israel AND Palestine, who built Caesarea and the palaces at Masada and the tombs of the Patriarchs in Hebron, who rebuilt the Temple where the Dome of the Rock now stands, atop the great platform bounded by the Kotel– was both a Jew on his father’s side and an Arab on his mother’s. Perhaps these great works, still wonders of the world after 2,000 years, can be seen as symbols of the greatness that could be created if Jews and Arabs worked together.

Shabbat shalom,

Rav Barry

For we and the Palestinians are part of one big dysfunctional family that goes back to Isaac and Ishmael, who struggled even in their mother’s womb.

Ishmael was 13 when Isaac was born. You’re thinking of Jacob and Esav.

The hopeful thing about the tale of Isaac and Ishmael is that despite living apart nearly all of their lives, they came together peaceably to mourn their father Avraham.

Hi Larry, you are of course correct…teaches me to write late at night! The post has been corrected…

Pingback: Interfaith Monologues | The Neshamah Center

Regardless of the stories on Aharon, I don’t believe he made an idol, period.

I agree, he would have heroically fought against it.