Vaera 5778 – Lessons from a Birmingham Jail

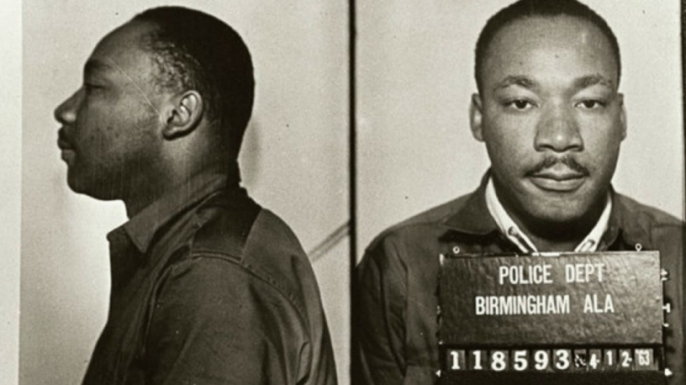

Fifty-five years ago this April, Martin Luther King, Jr., was sitting in a jail cell in Birmingham. King was from Atlanta; some questioned “what’s this outsider doing in Birmingham?” King’s response, in his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” was:

I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

King felt he had to respond to the call for aid.

A call for aid is the starting point for oppressed people seeking their rights. We see the same thing in this week’s Torah portion, Vaera, when God tells Moses,

וְגַ֣ם ׀ אֲנִ֣י שָׁמַ֗עְתִּי אֶֽת־נַאֲקַת֙ בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר מִצְרַ֖יִם מַעֲבִדִ֣ים אֹתָ֑ם וָאֶזְכֹּ֖ר אֶת־בְּרִיתִֽי׃

I have now heard the moaning of the Israelites because the Egyptians are holding them in bondage, and I have remembered My covenant.

It’s nice to think that such a cry would be unnecessary. It’s nice to think that as mankind evolves, we wake up on our own and would grant oppressed people their rights.

It doesn’t work that way. As Dr. King said, “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

The starting point for change is when the oppressed cry out. But, of course, crying out alone isn’t enough. Someone has to listen. Those of us in positions of power or privilege are charged with listening to the cries of the oppressed. And doing something about it.

What if we’re not the oppressors? Do we really need to get involved in something that’s “not our fight?” To put it somewhat crassly, if it doesn’t involve Jews do we have to care?

Yes, we have to care.

This is a lesson we can learn from Moses. In last week’s parsha there were three occasions when Moses acted righteously. In the first instance, an Egyptian taskmaster was beating a Hebrew slave. Moses killed the taskmaster. From this we learn that we should rise to the defense of a fellow Jew being attacked by a non-Jew. The second occasion is when Moses sees two Jews fighting, and he intervenes, seeking to break it up. This shows that we need to involve ourselves in seeking peace in disputes that are strictly among Jews. And the third occasion is when Moses gets to Midian, he sees some shepherds driving off women who were watering their flock. Moses rose to their defense, and the women, including his future wife Zipporah, were able to water their flock. From this we learn that we are also charged with intervening when there is an injustice among non-Jews. The biblical charge “tzedek, tzedek, tirdof,” “justice, justice, you shall pursue” means we must pursue justice anywhere we see an injustice, whether we’re personally involved or not, whether the injustice involves Jews or not. As Dr. King pointed out in his letter, we’re all interrelated:

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

Abraham provides another model for the need to speak up for others. When God tells Abraham that he’s going to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah because they’re so wicked, Abraham argues with God in one of the most chutzpadik passages in the Torah:

Will You sweep away the innocent along with the guilty? What if there should be fifty innocent within the city; will You then wipe out the place and not forgive it for the sake of the innocent fifty who are in it? Far be it from You to do such a thing, to bring death upon the innocent as well as the guilty, so that innocent and guilty fare alike. Far be it from You! Shall not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?

The prophet Jonah, I suppose, could also be seen as a kind of “outside agitator.” Jonah, a Jew living in Israel, gets sent (by God) to Nineveh, a non-Jewish town in Iraq, to save the people there, to warn them if they don’t change their ways they’ll be destroyed. Jonah wasn’t eager to save the people of Nineveh – in fact, when God taps him for the role he jumps on a ship headed for Spain, the opposite direction, trying to get as far away from it as possible. But Jonah couldn’t dodge his responsibilities, just as we shouldn’t dodge ours. We must come to the aid of oppressed or endangered people wherever they may be.

Dr. King wrote about how we’re all interrelated, and that’s a very Jewish teaching. It’s a message often repeated in the Jewish tradition.

The point is made with the very creation of people. The Torah says that mankind was created “b’tzelem Elohim,” in the divine image. All of mankind – not just Jews, or white people or brown people or any one group of people. We’re all created in the divine image. Not only that we’re all family – we all share common ancestors, Adam and Eve. And science confirms that we all have both a common male ancestor and common female ancestor.

The midrash brings a curious teaching on this point. There’s a famous injunction in the Torah, “And you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” R. Akiva says: This is a great principle in the Torah. Ben Azzai says: (Bereshith 5:1) “This is the numeration of the generations of Adam” — This is an even greater principle.

Why should “this is the numeration of the generations of Adam” be a greater principle than “love your neighbor as yourself?” There’s a meta-message in the seemingly boring genealogy, with all of its “begats.” The message that we’re all related. We’re all family. And everyone knows you’re obligated to come to the aid of your family member who’s in trouble.

All too often when there’s injustice, many of us just ignore it. Fail to pay attention to it. Dr. King addressed that “silent majority” when he wrote,

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

When I read the line about the white moderate, “who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice,” I couldn’t help but think of many of my fellow Israelis who don’t care about what happens to Palestinians in Gaza or the West Bank as long as there is the “negative peace” of no violence. That’s not enough. We need to strive for real peace, for justice.

There is no denying that Birmingham in 2018 is a very different place than Birmingham in 1963. Yet there is still much work to be done.

We may not even know the injustices that are right in front of our eyes. I was talking to someone the other day who grew up in Birmingham who said when she was little, no one gave much thought to segregation – colored water fountains and the blacks sitting in the back of the bus just seemed “normal.”

That’s why the oppressed need to speak up. They need to remind us that, “no, that’s not normal.”

Our African American neighbors are telling us there are still a lot of racial problems in America, in Alabama, in Birmingham.

And white people, for the most part, aren’t seeing the problems.

A Pew Research Center survey last year found that 38% of whites agree with the statement “our country has made the changes needed to give blacks equal rights to whites.” Only 8% of blacks agree. And the whites that don’t think we’re there yet, are at least optimistic that we’ll get there – only 11% of whites say the country will NOT make the changes needed to give blacks equal rights. Yet 43% of blacks – nearly half of all blacks – not only don’t think we have equality now, they don’t think they’ll ever achieve racial equality in this country.

An overwhelming majority of blacks – 84% – say blacks are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police. Only 50% of whites acknowledge what seems obvious to most black people. According to the ACLU, the government’s war on drugs has led to police pulling over black drivers in far greater numbers than white drivers in a search for illicit drugs. White people don’t talk about a problem with “Driving While White.” Yet many blacks, including veterans, professors, and sports stars, can tell stories about being pulled over for the crime of “Driving While Black.”

It’s not acceptable that 43% of blacks don’t think they’ll ever achieve equality in America. That’s not right. That’s not justice. We need to do better.

It’s only by listening to the cries of the disadvantaged that we’ll be able to live up to the ethical ideals of the Jewish tradition – and follow the example set for us by Abraham and Moses.

I close with the words Dr. King used to close his letter from that Birmingham jail cell:

Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Amen