Ki Tisa 5765 – Giving to Everyone

“And Aaron said to them, Take off the golden ear rings, which are in the ears of your wives, of your sons, and of your daughters, and bring them to me. And all the people took off the golden ear rings which were in their ears, and brought them to Aaron.” …Exodus 32:2-3

“And Aaron said to them, Take off the golden ear rings, which are in the ears of your wives, of your sons, and of your daughters, and bring them to me. And all the people took off the golden ear rings which were in their ears, and brought them to Aaron.” …Exodus 32:2-3

“Speak to the people of Israel, that they bring me an offering; from every man that gives it willingly with his heart you shall take my offering.” …Exodus 25:22

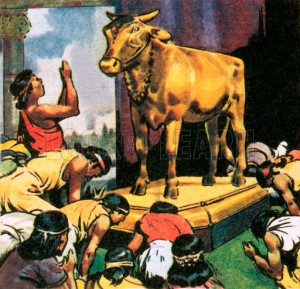

In this week’s parsha, Aaron asks the people to make a donation for the Golden Calf, and they give. In the Torah portion we read a few weeks ago, the people were asked to make a donation for the Tabernacle, the “portable Temple” and they gave.

In the Yerushalmi Talmud, Bar Acha comments on this: “It’s impossible to understand the character of this nation: they were asked to give for the Golden Calf and they gave; they were asked to give for the Tabernacle, and they gave!”

Is this a bad thing? Jews are among the most philanthropic of people–we’re big givers! Is it so bad if we’re sometimes a little indiscriminate?

Here in Toledo we don’t seem to have a lot of panhandlers. At least not in the parts of town that I frequent. Maybe the homeless people prefer bigger cities like Cleveland or Detroit where there are more resources; or maybe they move south to Florida for the winter: I would if I were homeless! But I think most of us travel to places like New York where there are panhandlers all over the place.

When you go to a place like New York where there are panhandlers all over the place, how do you treat them? Do you avoid giving money to any of them? Or do you give to all of them? Are you likelier to give to a woman? To someone with a child? To someone with a sign like “Need help. Willing to work. God Bless.” How about a sign that says “Hungry, need food?” What if the person looks like they have a drug or alcohol problem?

Many people act very judgmental in a situation like this. They either give to the one who is working because at least he¡¦s trying. Or they give to women but not men, or refuse to give anything to someone who looks like he might use it on drugs or liquor. Or as my daughter Katherine suggested in our discussion during services, on body piercings.

Our tradition, however, teaches us not to be so picky. According to the Rambam (Maimonides), “Anyone who sees a poor person asking for money who turns his eyes away and doesn’t give him tzedaka transgresses a negative commandment, as it is written, do not harden your heart, and do not close your hand from your poor brother.”

It is important to note that in formulating this commandment, Rambam tells us that not only does a person fail to fulfill a positive commandment to give tzedaka, but rather he violates a negative commandment, which is a more serious thing.

As a general rule, there is no penalty (at least not in this world!) attached to failing to fulfill a positive commandment. You are supposed to light Shabbat candles, but if you don’t, even in the days when the Jewish courts had jurisdiction over every aspect of Jewish life, you wouldn’t have been penalized or punished.

Violating a negative commandment is a different thing entirely. Unless otherwise specified, the penalty for violating a negative commandment was to receive lashes. Rambam taught that turning your eyes away from a poor person is a serious enough transgression to merit lashes.

You might argue, well, what if you’re poor yourself? What if you need help yourself? Do you still have to give?

The Talmud answers this question for us; in tractate Gittin, 7b it says:

Even a poor man, a subject of charity, should give charity.

What if you don’t have any change? What do you do then? Rambam tells us if you don’t happen to have any money in your pocket, you should at least give the beggar a smile and a kind word. When I see people looking for work, and I don’t have work, sometimes I’ll tell them that I’m sorry I don’t have any work for them.

As you evaluate whether to give money to different kinds of people, it might enter your mind to consider whether it makes any difference if you think the beggar is Jewish or not. Again, the Talmud in tractate Gittin provides some guidance: “Poor Gentiles should be supported along with poor Jews; the Gentile sick should be visited along with the Jewish sick; and their dead should be buried along with the Jewish dead, mipnei darchei shalom, for these are the ways of peace.” There is, however also a teaching that if your money is limited, it is OK to prioritize how much you give to different people, with family taking precedence over strangers, Jews over non-Jews, people from your town over people from another town, etc. But you still should give at least a little something to everyone.

We have been invited by the Multi Faith Council of Northwest Ohio to participate in a Habitat for Humanity build, a program through which volunteers donate time and money to actually build a house for a poor family. I am working with a few people who are interested, and I hope we will have a critical mass to participate. As that that teaching from the Talmud instructs, we need to contribute to the non-Jews in our community as well. In the past I know there was some question about participating in a build if the Muslim community is involved because of our political differences with them, and their refusal to condemn terrorism. But if we refuse to participate in a building a Habitat house because of that, who are we penalizing? The Muslim community or the poor family that the Multi-Faith Council is trying to help? If you are interested in participating in a Habitat build, please contact me.

But, back to beggars. What if you think the beggar is being lazy? Is it OK to question why he doesn’t have a job? Why doesn¡¦t he take advantage of the many resources the government provides? What if you think he might use your money to buy booze or drugs?

Rabbi Shmelke of Nicholsburg tells us, “When a poor man asks you for aid, do not use his faults as an excuse for not helping him. For then God will look for your offenses, and He is sure to find many of them. Keep in mind that the poor man’s transgressions have been atoned for by his poverty while yours still remain with you.”

We’re not appointed the judge over every poor person who comes our way. It’s not your job to determine whether every beggar you meet truly deserves your support or not. But, you might counter, it’s one thing to give money to a real poor person who might misuse–he is at least poor.

But what if he’s a fraud? We’ve all read stories in the paper of people who beg because they can make a lot more money than minimum wage if they’re good at it.

Rabbi Chayim of Sanz makes an important point about fraudulent charity collectors: “The merit of charity is so great that I am happy to give to 100 beggars even if only one might actually be needy. Some people, however, act as if they are exempt from giving charity to 100 beggars in the event that one might be a fraud.”

Of course, if you know for a fact that someone is a fraud, that he is not really poor at all, you are not obligated to give him money. Personally, I’ve never met a beggar who I was sure was a fraud. A few I might have suspected, but as Rabbi Chayim tells us, being suspicious is not a reason to refrain from giving.

One of the biggest challenges in giving tzedaka to beggars is that our tradition also tells us that it’s not enough just to give, rather we need to give gladly. In the eight levels of tzedaka, Rambam tells us that the lowest level of charity is one who gives to the poor person unwillingly; that someone who gives gladly and with a smile is at a higher level.

I grew up in New York City. Kids in New York are trained to be tough. We are trained from an early age to look away from all the creepy characters inhabiting the streets of New York. We are taught to look ahead, walk fast, and keep going. With some effort I’ve been able to train myself tobe much freer with my small change. But the part about acknowledging the other person, about giving a scruffy beggar a smile along with a quarter or fifty cents was a LOT harder.

Why does it make a difference how we give? Why shouldn’t it be enough to just give something and be done with it?

From the perspective of the poor person, it’s about helping them maintain their dignity even when they are in desperate circumstances. It’s not easy to be impoverished, and a smile and acknowledgement as a human being can be very important to helping a poor person’s self-esteem. The Torah is concerned with the dignity of poor people. Farmers are commanded to leave a corner of their field, and to leave behind forgotten sheaves, or areas they missed in harvesting for poor people. Why not tell the farmer to simply harvest everything and give a piece of it to the poor? Because it is better for the poor person’s dignity to harvest it himself.

There is, however, another reason why it matters how we give.

Giving tzedaka serves two purposes: the first is to support the poor who are needy. The second purpose of giving tzedaka, however, is to refine our own characters. To make us less selfish, less judgmental about the faults of others, more giving, to make us see the flaws in the world around us. To remind us that we are obligated to do something, even if it’s small.

If you live in a place like New York where there are a lot of beggars on the streets, you don’t have to give a lot to each one. Give what you can. Carry a roll of pennies or nickels if you can’t afford a roll of quarters in a place with so many poor people. But giving something will both do a little something to help the other person, and it will do a little something on opening your heart and helping you become a kinder more giving person.

Next time you see a beggar, don’t turn your eye–thank him in your heart for providing you an opportunity to do the mitzvah of giving tzedaka!

Pingback: Counting the Omer Day 15: Chesed of Tiferet - The Neshamah Center | The Neshamah Center